Why does your editor keep changing grey to gray in your book? You like the way grey looks. It’s listed in Merriam-Webster as a “variant spelling of GRAY”—that makes it legit, right?

Unfortunately, mixing American vs. British English doesn’t work that way.

For an everyday Joe, mixing English usage from all parts of the world creates no issues. If you like the way the Brits spell theatre, go for it; countless American theaters seem to think it looks more elegant and do exactly that.

But in publishing, conventions of usage characteristic of regional language (whether that’s American English, British English, Australian English, Canadian English …) are handled with more care. Amazon has been known to warn authors and even remove books from sale due to “errors” in books in cases of mixed American vs. British English. It’s an important detail for professionally published books.

My guest writer and British colleague Louise Harnby explains the beauty of British English—and why you don’t need it in your American novel.

Regional English: Graying out the differences

By Louise Harnby

I’m a sentence-level fiction editor. I’m also a Brit. My clients come from all over. It doesn’t matter a jot to me which kind of English they want to write in. You write behavior, I write behaviour—but unlike Fred and Ginger, we don’t need to call the whole thing off.

We don’t want your readers calling the whole thing off either, but that’s what can happen when a writer pulls the audience out of a story by peppering the sentences with unexpected inconsistencies.

And that’s where spelling variations can be problematic.

Not wrong, just different

The issue of variance versus correctness is an important distinction. It’s not that gray is wrong in British English but that it’s nonstandard.

And the same goes for grey in American English. Both variants have been around for centuries, long before anyone thought to standardize spellings on either side of the pond.

There are preferences, of course; you might just prefer grey to gray because you think it looks nicer. And there are personal nuances; I found one online American commenter differentiating between a soft dove gray but a harsh steel grey despite there being no evidence to support this distinction in any industry-standard dictionary or style guide.

Same with toward and towards, both of which mean “in the direction of.” Neither is right nor wrong. And there is no industry-accepted evidence to support a distinction in meaning or level of formality implied.

However, toward is far more common in American English. We Brits, on the other hand, tend toward towards. (It makes me itch not to put an s at the end of the penultimate word in that sentence, but I’m writing for my American friend so I’m respecting the corpus!

Language that serves the reader

Here’s the thing. Your preferences and my nuances mean nothing. When it comes to novel craft, it’s all about the reader.

And that’s why likes of the Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster tell us not what’s right but what’s standard. Dictionaries record usage.

Google Ngram has gray taking the ascendancy in the US from 1826. Over in Blighty, we’ve been greying our way through the written word since 1698.

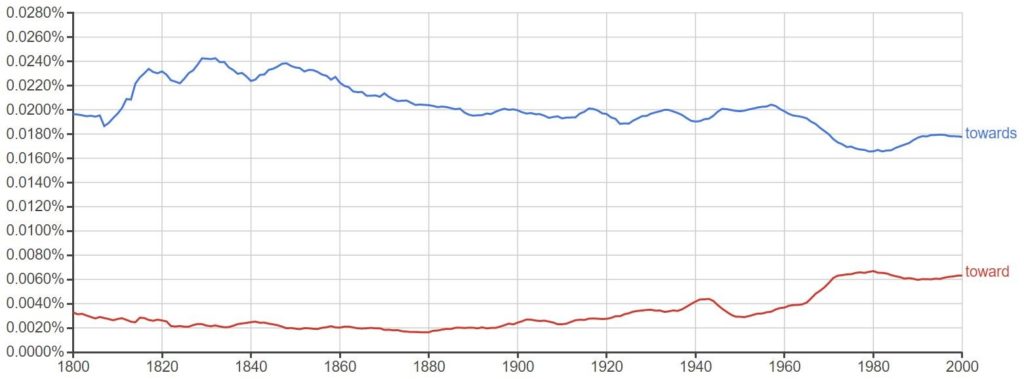

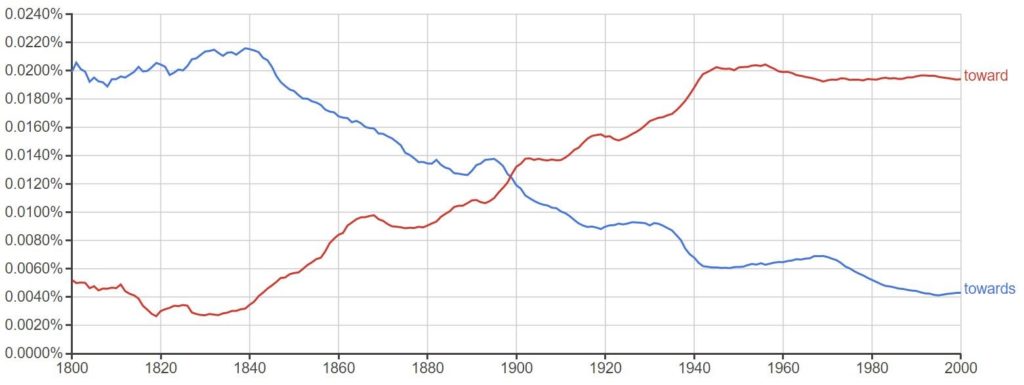

And take a look at what’s been happening with toward and towards in our two Englishes over the past two hundred years.

British English

American English

Ngram isn’t perfect by any stretch of the imagination, but it gives us a snapshot of how people write and what readers expect now. Why does that matter? It matters because, for the most part, where your readers live determines what they expect to see in your novel.

And if you insist on putting your own preferences first, Fred and Ginger get angsty.

How far will readers bend?

I’m not saying readers aren’t flexible. If a novel’s written in British English, fine. American English, no problem. But a mixture of the two? The reader who doesn’t know the variants or industry-recognized standards won’t notice and won’t care. They’ll bend any which way.

The problem is the readers who do know. They won’t see your preferences; they’ll see mistakes. They’ll think you didn’t hire an editor, or you did but you didn’t take the editor’s advice, or you did but the editor was rubbish.

Ask yourself this—do you want your readers thinking about the degree to which you invested in quality control for your novel, or do you want them immersing themselves in the world you’ve built and the characters who move around in it?

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, Amazon didn’t exist and there were no online reviews. Grumpy readers who thought you’d spelled something wrong might have moaned to their neighbor or, if they had time on their hands, crafted a letter of complaint and sent it to the publisher via the mail. In a real envelope. With a stamp on it.

Not so these days. It takes mere seconds to reduce your punchy plot, perfect pace, and nifty narrative to a debate about how one spells p(a)ediatric, dra(ugh)/(f)t and behavio(u)r in standard American or British English.

And it’s not just the grump who gets to have fun. It’s all the other people who might have been your fans but decided not to buy your book because of the grouchy reviews. Worse still, it’s not just this book that’s affected but all the books you’ll ever write.

American vs. British English

If you’re not sure what’s standard, that’s fine. A professional editor will know, or they’ll check if they’re unsure. That’s their job.

The wise author listens to the editor. And the wise editor can back up her guidance with evidence and a sound knowledge of publishing-industry preferences, expectations, and standards.

We’ll respect idiom and slang, of course, but when it comes to words for which there is evidence of spelling convention, let us guide you.

It’s not that we’re being pedantic or stuffy but that we want you to succeed. We want your fans to cherish your book, rave about it, recommend it, and focus on what’s important—the gift of your story.

A quick word on -izationing

If you decide to write your novel in British English, feel free to let loose with the z (though take care with some verb forms—analyse, paralyse, for example).

Contrary to what many think, the -iz variant is not American spelling. It’s an accepted and widely used BrEnglish variant that’s been knocking around my neck of the woods for a while now—since the 1500s, in fact. It’s my preferred spelling and the chosen variant for numerous British publishers, especially academic presses and the mighty Oxford English Dictionary.

In a nutshell

It’s a gre/ay old world but I’ve trave(l)led far and wide in my mind to move toward(s) a conclusion to this blog post. In my defenc/se, my arguments are colo(u)red by a desire to focus on not what is right but what is expected.

It’s hard enough to mo(u)ld a story that grabs readers’ hearts and minds; getting the wool(l)y spelling on point so that readers aren’t reaching for the tranquil(l)izer gun is another headache but one worth attending to.

If you’re serious about building a loyal audience, put Fred and Ginger first. Be consistent and respect convention. Spell in a way that’ll keep their attention on your story.

And bear in mind that we Brits like to make things complicated for ourselves. I’ll pass judgement on you—unless I’m a British judge, in which case I’ll be offering you my judicial opinion without the middle e.

And in case you’re interested, we like an s when we’re licensing and practising but are strict about a c when it comes to the noun (practice and licence). All of which means that if I were a legal professional, I’d be practising good judgment in my licensed legal practice … as long as my licence is up to date. Just so we’re clear.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader’s Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Louise Harnby is a fiction copyeditor and proofreader. She curates The Proofreader’s Parlour and is the author of several books on business planning and marketing for editors and proofreaders.

Visit her business website at Louise Harnby | Proofreader & Copyeditor, say hello on Twitter at @LouiseHarnby, or connect via Facebook and LinkedIn.

If you’re an author, take a look at Louise’s Writing Library and access her latest self-publishing resources, all of which are free and available instantly.

Understanding how stories work changes everything. I’ll show you how to back up your creative instincts so your ideas hit home. It’s time to accelerate your journey from aspiring writer to emerging author.

Ready to get serious about your book? Apply to work with me.